What Really is Marxism?

Marxism, though correctly associated with communism, is a deeply misunderstood word in many ways.

Though not a Marxist myself, I find Marx’s works relevant and interesting. However, a lot of people seem to misunderstand what “Marxism” even means. It is often correctly associated with communism, the economic system that it advocates. However, to say Marxism is communism is a grand oversimplification, and most of what people think of as “communism” is specifically Marxism-Leninism. To see Marxism solely through that lens would be like trying to understand Christianity while ignoring Catholicism entirely.

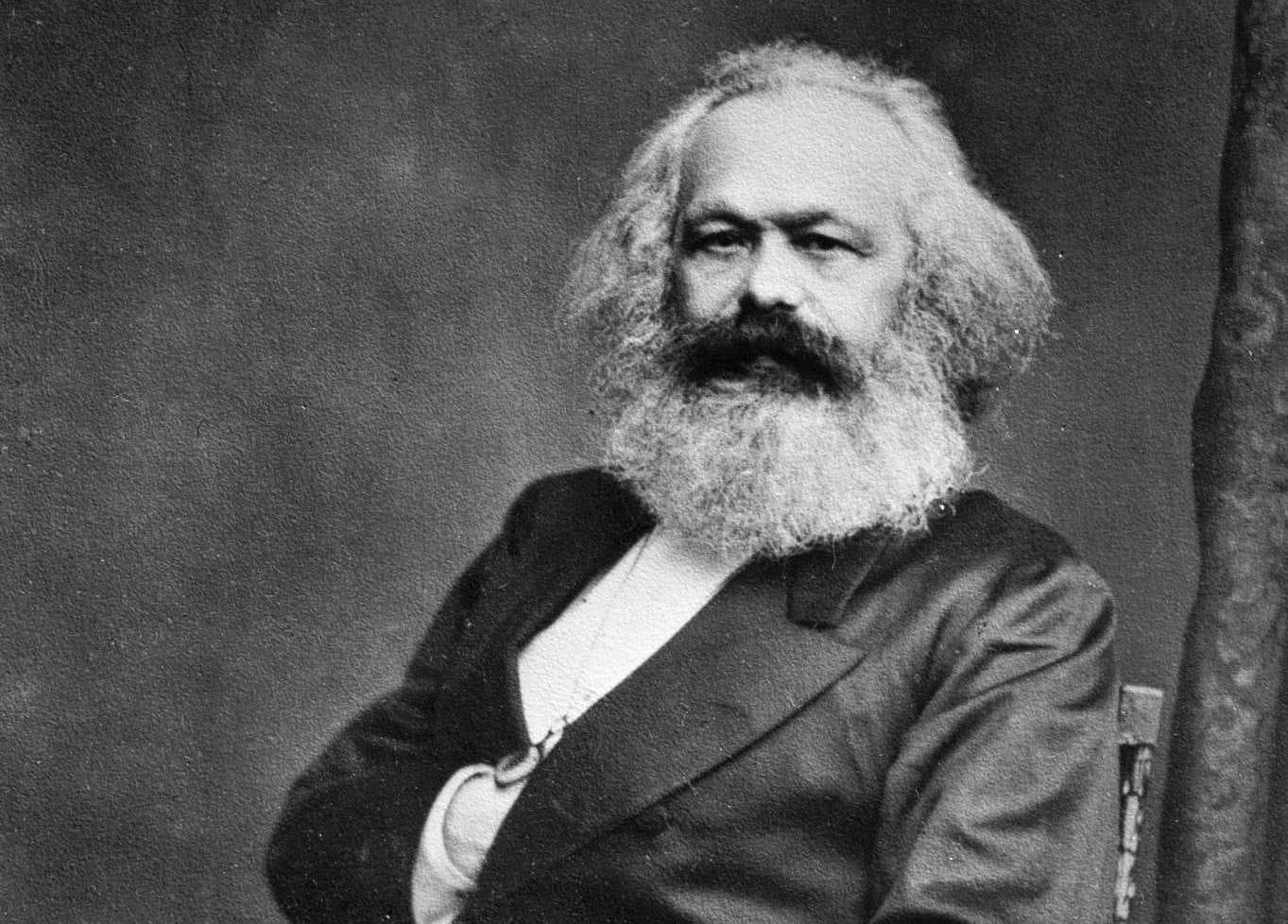

Surprisingly to some, Marx was a man who praised capitalism as the most innovative economic system ever implemented whose best friend was a prominent member of the bourgeoisie, the son of the extremely wealthy textile manufacturers. Marx even made a lot of money on the stock market investing his friend’s money. Exaltation of this bougie friend, Engels, is common among Marxists, even among Marxist-Leninists. The USSR even founded The Marx–Engels–Lenin Institute.

Orthodox Marxism frames capitalism not as evil but rather as a step in socioeconomic development that greatly improves the “productive forces” of a country — in other words, the ability of a country to produce useful goods. This can be increased both through innovations in production via industrialization and the increased technical skill and specialization of large swaths of the workforce this enables. Marx expected that it would be the advanced capitalist countries that would pave the way to socialism, given the immense productive forces capitalism built, which would support a robust socialist system. Though Marx thought capitalism to be exploitative, he saw it as a massive improvement over systems like feudalism that came before.

Marx’s most famous work, Das Kapital, has very little to say about socialism and instead picks apart the way capitalism functions in minute detail. Marx, through analysis of history, argues that real world material conditions, which are directly linked with economic systems, are what drive change — “matter in motion.” This is in contrast to conceptions of history where ideals or Great Men drive history. This is kind of ironic, given how much impact the ideological ideals of Marxism and the personality cults of Marxist-Leninism had on the world.

Enormous emphasis is placed on contradiction and dialectics. The present emerges from syntheses of the theses and antitheses embodied in these contradictions. Das Kapital documents the contradictions of capitalism in detail, making the overall argument that the dialectical process they would induce would inevitably result in socialist revolution. Marx saw the Civil War and the abolishment of slavery, which happened in his lifetime, as an example of this process — revolutionary even if not a socialist revolution — and shared correspondence with Lincoln.

Where Lenin departs from classical interpretations of Marx is around the impacts of imperialism. Though in prior centuries, imperialism was usually a product of conquest and more classical forms of colonization, Lenin argued capitalism had innovated. Private corporations could export their capital across borders to other countries, where it can be used to buy up land and natural resources as well as create bases of cheap manufacturing, given the much lower costs of labor in many countries.

Lenin uses this phenomenon to argue that Marx, while right about most things, was crucially wrong about one. He argued that advanced capitalist countries will be too enriched by imperialism for there to be revolutionary potential in them, and the countries they imperialize will be sucked dry of resources too much to develop the productive forces necessary to support communism. Therefore, Marxism-Leninist countries typically reject the capitalist phase and immediately begin rapid industrialization, seeking to up productive forces as fast as possible.

Lenin clearly had a point about the revolutionary potential of impoverished countries, but Marx also had a point about productive forces. Marxist-Leninist states routinely struggled with shortages of critical supplies and a wide array of problems caused by rapid industrialization. Their environmental records are generally worse than capitalist ones — Chernobyl’s design was picked for its low cost and quick construction time, despite knowing it was more prone to meltdown.

That’s not to say that Marx himself thought the poor in impoverished countries were without revolutionary potential, remarking later in his life about how much of it he saw in the Russian peasantry. What many miss about the Russian Revolution, though, is that it happened in two stages. In February, the tsar was overthrown by — you guessed it — the peasantry, predominantly. They implemented a representative republic dominated by reformists who wanted a gradual transition to socialism. This, however, did not last long. In October, the Bolsheviks overthrew the republic and created the first Marxist-Leninist government.

Marxism has a concept called the “dictatorship of the proletariat,” which Marx made clear is not meant to be a dictatorship in the sense the word might normally conjure. The highly democratic — though, admittedly, short-lived — Paris Commune was cited as a model for how such a system should work. His goal was never to make the state a stand-in for the workers, but to truly give workers meaningful control of the state. The Paris Commune also quite rightly burned the guillotines, despite the fetish a lot of modern leftists have for their imagery.

Marx defined communism as a stateless, classless society. This did not mean he wanted immediate abolition of states, however, and saw the power states wield as critical to implementing much of the work necessary to get the result he advocated. Lenin seemingly agreed with this. But the ideology of Marxism-Leninism was codified not by Lenin, but by Stalin after his death — the same Stalin who heartily embraced personality cults, intentionally worsened a famine in Ukraine, and came up with the idea of “Socialism in One Country.” Whereas Marxism is supposed to view nationalism as, at best, a means to an end, Stalin saw it as an end in itself.

Marxism, Lenin’s additions to Marxism, and Stalin’s politically expedient framing of his nationalistic vision as Lenin’s all are unique phenomena, but each served as influences on what became the USSR and every self-described communist country to come since. But, looking at these countries, one would be baffled at the idea that Marx eventually wanted a stateless, highly democratic world. With how many self-described Marxists treat capitalism as the source of all evil, the fact Marx saw it as a useful and innovative phase of economic development on the road to socialism surprises many.

In present usage, “Marxism” is intentionally often used not as a meaningful term, but a scare word thrown around by reactionary members of the GOP eager to slander people like Biden as something that they obviously are not. Regardless of whether you see it as a good or bad thing, nothing about the Democratic Party is Marxist in nature. Even people who are Marxists are so often not what people assume, even if the much more authoritarian Marxist-Leninists still exist as well — as anyone who has spent any time discussing socialist politics on social media can report.

Marxism, though heavily focused on the development of communism, encompasses areas like analysis of other economic systems and the study of dialectic and historical materialism. Marx was a man of nuance who understood the beneficial role capitalism could play in the development of an economy as well. However, much as trying to understand Marx entirely through the lens of entities like the USSR is like ignoring Catholicism in the study of Christianity, self-described Marxists, much like self-described Christians, many times do not embody what their ideology claims to support. Judging that is up to you — and maybe now you are a bit more well-equipped to do so.