Revisiting The Yes Men

The culture-jamming performance artists who first came to prominence in the early 2000s can teach us a lot about the power of performance art.

In 2005, I sat down for what I thought was just going to be another informative but not particularly exciting documentary — the month-end ritual for our AP Human Geography class. What followed blew my mind. The Yes Men, the 2003 documentary that wound up the first of a trilogy about culture-jamming activists of the same name, immediately impacted my view of the intersection of politics and performance art. The film, though silly — it even includes an inflatable suit with an enormous penis pitched as a serious product — explored the deep power in using strategic dishonesty to elucidate important truths.

The Yes Men’s methods have spanned both the digital and physical realms. One of their earliest works of culture-jamming performance art dates all the way back to the 2000 presidential election, when they managed to snag the domain gwbush.com and launch a fake campaign site that, at first glance, could easily be mistaken for the real thing. However, it included falsified interviews and policy proposals that were intended to reflect the reality of W’s awfulness and the direction of conservatism in America – concerns proven right time and time again by the rise of Trumpism. It gained enough notoriety that Bush was asked about it in interviews, and he even wound up trying to involve the FTC in shutting them down.

This idea was the brainchild of Zach Exley, who bought the domain and reached out to two men who were behind a 90s internet forum called RTMark going by the aliases Mike Bonnano and Andy Bichlbaum. The goal of the online community was to organize creative political activism that challenged corporate power. Their most notable antic involved buying a bunch of Barbies and G.I. Joes and then returning them with their voice boxes swapped, challenging the gender norms of the toy industry. During this era, Bichlbaum, a gay man and a software engineer, was working at Maxis, where he secretly added code that would make a horde of shirtless gay men in speedos spawn in SimCopter, not just to draw more attention to LGBTQ+ issues but also to protest the crunch culture that existed in the gaming industry even back then.

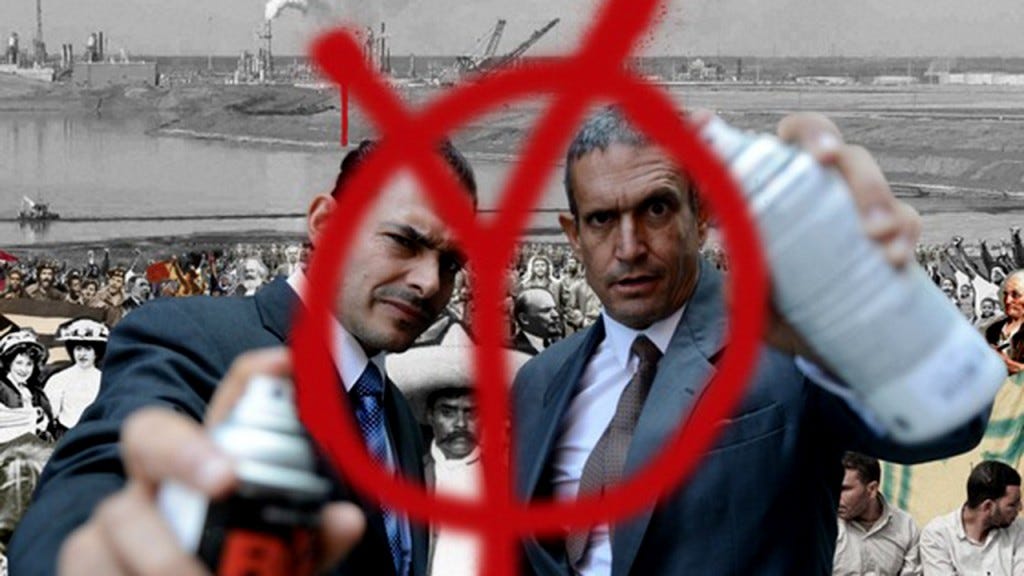

This meeting of the minds led to the creation of The Yes Men, with Bonnano and Bichlbaum serving as its public faces, continuing RTMark’s legacy of challenging corporations while expanding to challenge unjust government power as well. They codified their approach as “identity correction” — portraying themselves as official representatives of these concentrations of power and using their falsified identity to say what should be said, even if it is not the actual truth.

Though they continued and expanded their anti-Bush prankery during the 2004 election, their biggest source of notoriety that year — and arguably ever — came elsewhere. Bichlbaum forged false credentials establishing him as “Jude Finisterra,” a supposed PR spokesman for Dow Chemical. BBC eagerly invited him on for the chance to make a special announcement. Finally, The Yes Men had managed to find an audience like they had never had before.

In 1984, a pesticide plant in Bhopal, India owned by Union Carbide experienced a catastrophic accident that killed thousands of people while contaminating the surrounding area with dangerous chemicals. Union Carbide paid a fine to the Indian government but never compensated the victims or cleaned up the mess left behind. Even now, forty years later, the site of the accident is still dangerously toxic. Union Carbide ultimately was bought out by Dow Chemical in 2001. While the disaster was covered in Western media, ultimately, because it did not affect Westerners, it was far too easy to just be swept under the rug and forgotten.

But about halfway between then and now, on the twentieth anniversary of the disaster, The Yes Men were passionately determined to bring attention to this disaster once more. Suddenly, for the first time since the immediate aftermath of the disaster, the stakeholders behind the project were speaking — or so everyone thought. “Finisterra” announced Dow was admitting that their now-subsidiary Union Carbide was at fault for the accident and would take full responsibility for what happened, including paying money to victims and for the cleanup of the contaminated plant site.

In less than thirty minutes, billions of dollars were wiped off of Dow’s market cap. Much as the ethical thing to do would be to accept their “corrected identity” – and, perhaps over a long enough time horizon, the right thing to do for business – Dow refused to play ball. Adamant to continue to make them pay for their unwillingness to do the right thing, Bichlbaum started posing at conferences as "Erastus Hamm," where he would demo Dow’s “acceptable risk calculator,” software that determined just how many people a corporation could kill without harming profits, represented by a golden skeleton as a mascot.

Sadly, even now, twenty years after their stunts and forty years after the original disaster, Dow has refused to do the right thing. However, The Yes Men were credited with bringing a renewed and particularly biting focus on the disaster that had not existed previously on Western television news. As revealed in the later Stratfor Leaks, Dow was so bothered by The Yes Men’s antics they hired the private spy agency to track their movements and activities, for fear of further identity correction.

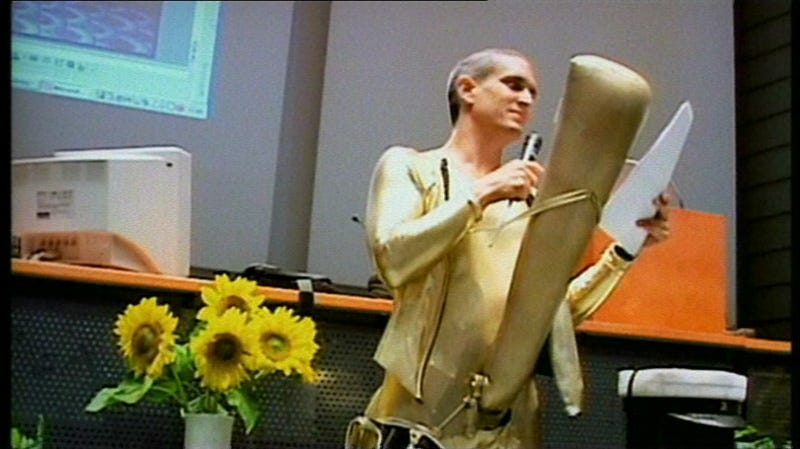

At times, The Yes Men have opted for more silly methods of culture-jamming performance art while always maintaining their edge. As the World Trade Organization, they unveiled the “Employee Visualization Appendage,” a gold suit with a giant inflatable penis attached with a screen on the end, designed to make it easier to monitor factory workers in “shithole countries” making mere pennies per hour. As Haliburton, they announced the “SurvivaBall,” an inflatable orb that is designed to make it easier to withstand the devastating effects of climate change.

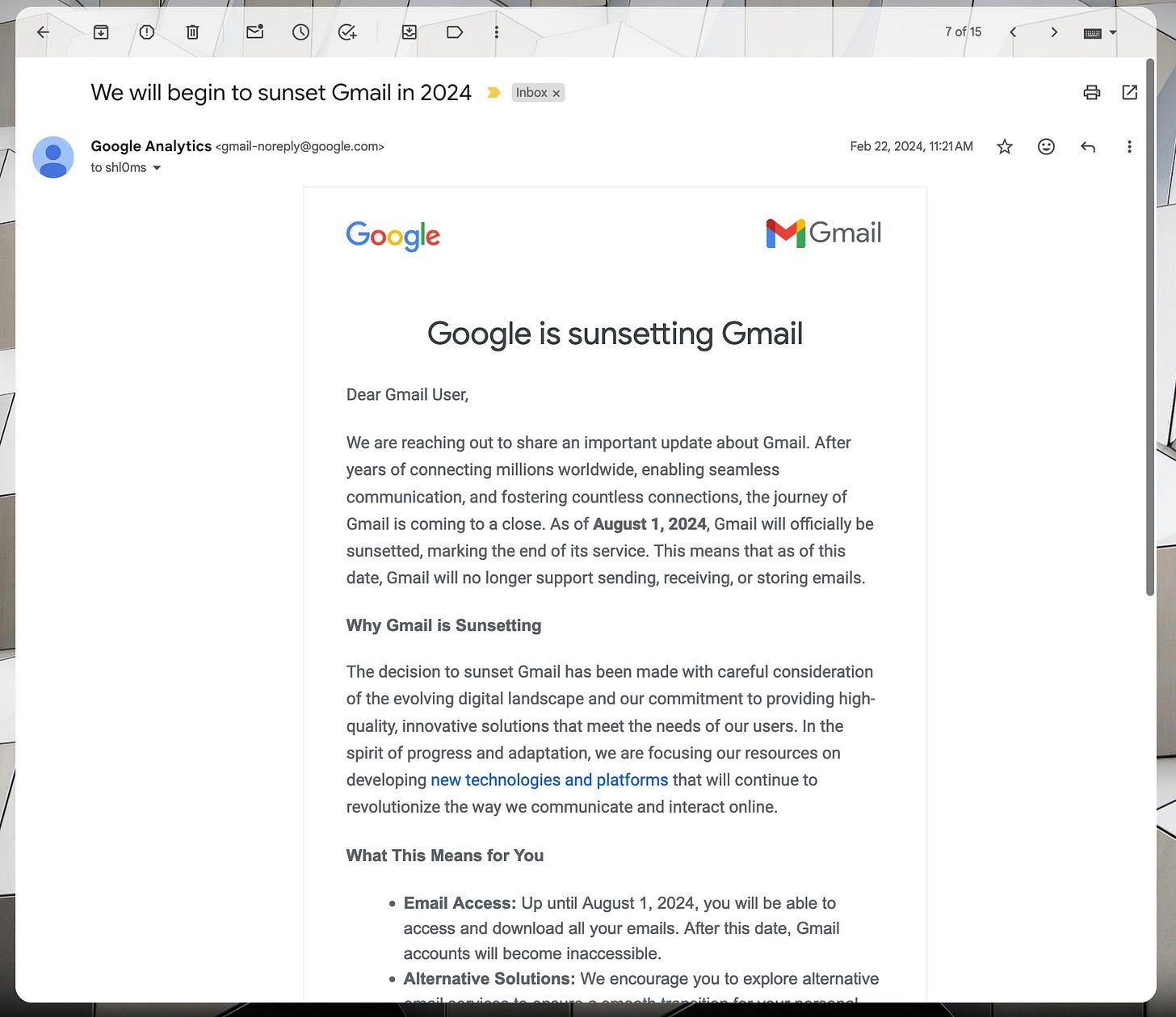

Many readers might be familiar with a recent claim that GMail would be shutting down, which spread like wildfire virally throughout the internet. The origin of this claim is SHL0MS, a performance and conceptual artist I have praised in this publication before. His goal was not to spread mayhem for the sake of mayhem but to prompt deeper examination – we have given a massive corporation so much power over our lives in ways they could inconvenience us at a moment’s notice. It was especially believable given Google’s penchant for pulling the plug on products as soon as they no longer prove a massive boon for Google’s goals. It is thus entirely fair to describe SHL0MS’s antics as identity correction, much in the vein of The Yes Men.

Frankly, in an era when corporations are wielding more power than ever and governments grow increasingly authoritarian, we need a lot more identity correction to help level the playing field between those with power and those without. Though critics will undoubtedly dismiss it as pointless pranks and disinformation, it leverages the power of virality to help spread a message that otherwise not be heard. Though The Yes Men may be masters of their craft, they can only do so much — and are getting older. Ultimately, all of us can learn from them and adopt their techniques. Power to the political pranksters!